“I feel like it’s not me who chose the subject, but the subject chose me.”

— Wangari Mathenge

A lawyer and painter, Wangari Mathenge has in her fascinating oeuvre openly documented the lived experiences of Black people. Her focus is mostly on Kenyan women, and she emphasizes the visibility of women despite their cultural suppression. In her work, she depicts women in their domestic surroundings, and she deploys concepts of togetherness, of sisterhood, and what a safe space could mean for women’s empowerment.

Ugonna-Ora Owoh How has it been living in the US all these years?

Wangari Mathenge I left Kenya in the late 1990s. I was very excited to leave, mainly because of the freedom of not being with my parents.

UO You left without your parents, or you left on your own?

WM I left alone. I was born in Kenya, and then six weeks after I was born, we moved to the UK as a family and then moved back to Kenya. But because I was so young when we lived in London, I don’t really have a primary memory of that. I left Kenya when I was twenty. All my formative years and everything was in Kenya. I studied at my primary high school and my first degree. For me, I think leaving was more just to be able to express myself. I wanted to feel what it would be like to make my own decisions on a day-to-day basis. I came to the US to pursue my master’s. When I came, it was straight to school and rigorous. It’s not like I had much freedom because I was busy studying all the time. I don’t think there was a culture shock for me, maybe because I was already immersed in Western culture. Which is so unfortunate. I wish there was a culture shock. I remember the first time I went to New York City, and I was like, It’s exactly like I imagined it in the movies. I definitely remember saying that I learned how to talk in America. I found my voice, and I found my ability to vocalize things because I did not realize, but culturally as women we were made to not talk at all. We even have this thing culturally that when a goat is slaughtered, there are certain parts of the meat that men eat and certain parts that women eat. And the women are given the ear so that they can listen. I think the men eat the tongue so that they can speak.

UO That’s really crazy.

WM Yeah, it’s crazy. But this actually does affect how you see the world and how you interact with the world. It’s so symbolic of your function, your role. After living in the US for so long, I remember returning to Kenya with my husband. I was in a social setting, and I told him, “Hey, could you go get me a cup of tea?” and people looked at me like, Are you crazy? I don’t know, but the rules are just so generic and not supposed to exist. It makes us feel backward, like we are living centuries ago.

UO Was that part of what prompted your exploration of female empowerment in your work?

WM I would say that was not overly premeditated. I was in Kenya during Covid for an extended amount of time. My mother wasn’t feeling too well. And so I decided to spend some months there to make sure that she was okay before I left. One day I was watching media depictions of domestic workers and their plight, especially in the Middle East. I remember hearing these stories about how they go there, and it’s a form of entrapment. They think they’re going to do maybe one job, and then they get there, and they’re sold into sex trafficking. Or even if they go there to work in domestic care, it’s in a relatively abusive relationship and oppressive. Their passports are seized, and maybe they’re not compensated the way they are supposed to be compensated. When I started hearing about these stories, I started thinking about the domestic workers who are within Kenya and how they tend to be almost invisible.

UO So the A Day of Rest (2022–23) series was spotlighting these domestic workers.

WM Yes. Of course, domestic workers can be female or male. But I wanted to celebrate these women because women also have a double role of not only working, but they also probably have children. And I just thought that, generally speaking, they can be the most overworked. It’s easy for me to relate with other women and to relate with their experiences. When people ask me, Why Kenyans? Because I’m Kenyan. Even if I have lived outside of Kenya longer than I’ve lived in Kenya, I’m still a Kenyan. These are my sisters. These are my relatives. I feel like it’s not me who chose the subject, but the subject chose me.

UO Tell me about the works in your current Nicola Vassell exhibition.

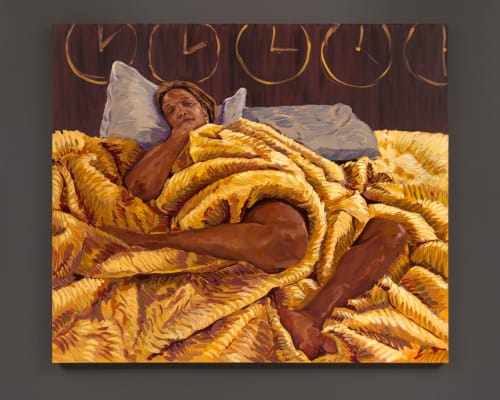

WM The exhibition is a series of paintings that revolve around the themes of hypnagogia and hypnopompia.

UO That’s very interesting.

WM Yes. Hypnagogia is the state of being in an alternative dream state. It’s the state as you are falling into sleep when you have hypnopompia, which are the dreams that may occur during sleep. Hypnopompia is similar to hypnagogia. I want to create awareness around it. And it’s also a way of me exploring it as an event that has happened to me because I realized that it’s actually quite unique. My husband doesn’t have it, and everybody I’ve asked hasn’t experienced it. But some people have said they’ve experienced hypnopompia in one very common sense.

UO Is it like sleep paralysis?

WM Yes, exactly. Sleep paralysis. Has that ever happened to you?

UO It has never happened, but I heard it’s a crazy experience.

WM Because I realized that hypnopompia is quite a unique experience, I started documenting it. I put cameras around the house, and then I also had a notebook. Every time I would experience one of these things, I would write it down. Then at some point, I thought this would be an interesting subject to explore for a show. And I also have video work accompanying it, which includes painting animation and some digital animation. It will help expound on the nature of these experiences so that the audience is more immersed in the experience.

UO Aside from sleeping, did you listen to a lot of music for the exhibition?

WM When I create in the studio, I listen to music. I love music. In fact, I always say, weirdly enough, that despite being a visual artist, I choose music over art. I can’t live without music.

UO Exactly. It’s the same thing for me. What artists are you listening to at the moment?

WM That question has been posed to me so many times. Would you believe that every time I struggle to answer because I listen quite broadly? I’ve had phases. There’s phases when I listen to rap or something else. Right now, I really like indie and alternative. And I think for me, it’s because of the stories they tell. I like music that has quirky stories. I’m listening to Future Islands.

UO Are they an indie band?

WM They are alternative, that’s for sure. I would say mainstream to some extent. I saw them at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago, and they said that was the biggest venue they’ve sold out. I love their music. But in terms of music, I like two songs from this artist, two songs from that artist. That’s why I find it hard to pick a favorite.

UO You don’t have a loyalty to one particular artist?

WM I don’t know that there’s one who I’m into deep, deep, everlasting, forever. Unlike most artists, I can’t access jazz. And that I say without any fear.

UO You don’t love jazz?

WM No, I don’t love jazz. I’ve tried. Because every artist I know is like, Oh, you’ve got to listen to jazz. And I’m like, This life is short. I’ve decided that I just have to live my truth, which, by the way, goes to your question about philosophy. My philosophy is just to be true to my capabilities, to my wants, my desires, and to block out expectations.

Wangari Mathenge: Bedimmed Boundaries: Between Wakefulness and Sleep is on view at Nicola Vassell Gallery in New York City until October 19.