As Ming Smith's solo Frieze LA show with Nicola Vassell debuts today—which runs concurrent to her show at the Studio Museum in Harlem, "Projects: Ming Smith"—the photographer sat down with her friend, the curator Thelma Golden, to discuss encapsulating Harlem and the chance encounter that sparked their relationship.

For Thelma Golden, Director and Chief Curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem, few artists can better Harlem's essence than Ming Smith. For years, the Detroit-born, Harlem-based photographer has harnessed the power of her keen eye and quiet watchfulness to reveal intimate moments in the lives of our culture's most iconic and and complex figures, alongside fleeting interactions on the streets of her adopted neighborhood. For Smith, who made her way to Harlem after graduating from Howard University, life as an artist begins and ends with the Studio Museum. "Before I even went to the Studio Museum, it was already in my heart," she says, recalling a Kamoinge show at the institution that she visited when she was still new to the city. There, she found herself immersed in a community of Black artists, musicians, and performers who were supporting one another's work at a time when the rest of society refused to do so.

Things have changed since those years. The museum, founded out of a rented loft in 1968, later opened up shop in the former New York Bank for Savings in the ‘80s, and now has taken up temporary residence at the Museum of Modern Art while its new building is under construction on West 125th Street. Smith, for her part, opened "Projects: Ming Smith" as part of MoMA's Project Series in collaboration with the Studio Museum. The project, curated by Golden, offers a deep dive into the artist’s archival material, spotlighting images of Harlem. Up next, Smith will present a solo show, "The Things She Knows," a selection of new and little-seen works, at Nicola Vassel's Frieze booth. On the occasion of these two momentous exhibitions, Smith sat down with Golden for a conversation about chance encounters on the street, making art from life, and the neighborhood where it all started.

CULTURED: Tell me how you first crossed paths.

THELMA GOLDEN: I've known Ming's work for as long as I've known artwork. At the beginning of my career, when I had the privilege to intern at the Studio Museum in Harlem and work at the Whitney Museum of American Art, I had the occasion to see Ming's work in various contexts. Since those initial moments of encounter, her work has stayed with me. It was a great pleasure to then meet her, many years later. Ming, when did you meet me?

MING SMITH: Actually, I was following her down the street. I was like, “Who is that?” Someone said, “That's Thelma.” She had this swag, and she was dressed beautifully. She always looked so beautiful—even now, I don't know how she does it. She has to make so many decisions, and she doesn't ever look anxious. She's always calm. She has a sense of humor and a love that’s very nurturing. But actually, it was her swag that I noticed first.

CULTURED: So, right there on the street?

SMITH: Yes, in Harlem, on 125th.

GOLDEN: [Laughs] That's right. That was amazing because, of course, I knew her practice—but to actually meet her and learn we were living and working in the same neighborhood, instantly became an important part of how I understood being in Harlem.

CULTURED: Thelma, I'm curious about your first impressions of Ming, and how they connect to the work that she's been making for so long.

GOLDEN: Through my encounters with her work, I understood that Ming offers us an entire universe in the work. She has a capacious eye that is constantly capturing moments but is also entering into so many worlds. When I met her, it didn't surprise me that she had this incredible, grounded presence. I could also feel the broad glow of her sense of self and her spirit. To speak to Ming is to understand the ways she sees, and that's what's so profound in these works, right? How her eye manifests in these incredible images.

CULTURED: Ming, your work has been shown at the Studio Museum since the beginning of your career. Could you talk about your experience appearing in early exhibitions there in the ‘70s and ‘80s?

SMITH: First of all, from the very beginning, the Studio Museum was a place to show Black artwork when no one was showing it. Before I even went to the Studio Museum, it was already in my heart. I remember Kamoinge had this group show there that I went to when I was new. I saw people like Ed Clark and Jayne Cortez and Elizabeth Catlett and Samella Lewis and Albert Murray, Black writers and some musicians. Max Roach, he was a musician. Any time Elizabeth Catlett had an exhibition; he would be there. But, he was also a dancer with Arthur Mitchell. Romare Bearden was there. A lot of these Black artists, I didn't know their faces then. These are people that I love, that I had seen just little bits of their work, such as Hughie Lee-Smith. I was so intimidated by all these artists. The energy was incredible; there was so much love and respect for Black culture. It was authentic. There was no other place that I knew of that was in celebration, and it was authentic, because unlike today, it wasn't like people were making millions of dollars. They were doing it out of the love of the culture, to bring understanding—not only to our own community but to the world, and they were very generous. They were very generous and giving. They welcomed the young artists, and it wasn't competitive. I didn't feel any of that. It was more an exchange of ideals and energy, which is unique. It wasn't like they were doing this so they could have a show with the Museum of Modern Art or the Guggenheim, it wasn't that. It was out of real, authentic motivation.

CULTURED: How did entering that world so early in your career shape your perspective as an artist?

SMITH: Oh, it was life-altering. Samella Lewis and Elizabeth Catlett, they were friends. Samella was an artist, but she also wrote books about and supported different artists. I didn't know this when I first met them, but they were together. I found out about their relationship whilst I was living in LA—I visited Samella, and Elizabeth was there. She was in her 90s or late 80s by then, and I hadn’t seen them for maybe 50 years. They were just as close as they were back then. I really admired seeing two female artists, women, still together after all those years. Yeah, that was the Studio Museum.

CULTURED: Thelma, how did you approach Ming’s archive while curating "Projects: Ming Smith"?

GOLDEN: It's important to be clear about the origin story here. Since the Studio Museum in Harlem closed in 2018, we've had an incredible partnership with the Museum of Modern Art. It's given us the opportunity to present exhibitions while we construct our new building, designed for us by Sir David Adjaye with Cooper Robertson, which is rising on 125th Street as we speak. This is our fourth exhibition with MoMA in the Museum’s Projects space, which is open to experimentation of presentation. In my work as chief curator and director of the Studio Museum, I have revered Ming’s practice—as she said, she lives deep in our history, and in many ways my understanding of our history comes from her ability to give me a sense of what the Studio Museum is. That inspired how I hope to lead and what I hope to make the Museum.

I became interested, specifically in relation to our collection, in Ming’s images of Harlem. At the Studio Museum in Harlem, we’ve been building a collection of images of this historic, iconic neighborhood through the eyes of photographers across the last century and into this one. Some years ago, that led to an acquisition of some of Ming's Harlem works. At that moment, I knew I wanted to spend time in her archive. Fast forward to today—the MoMA partnership presented an opportunity to think about Ming and go into the archive. Our collaboration with Oluremi C. Onabanjo made this project happen. Oluremi has been the absolute intellectual and curatorial heart of this process. For all of us, this has been a wonderful opportunity to engage with each other. Ming, you might think that story is different but—

SMITH: No, that was beautifully put.

GOLDEN: As we began to be in rooms together again, we engaged tentatively with each other. Being together in a room—going through Ming's archive, looking at prints, listening to her—allowed us all to learn so much about her work. I’ve had the privilege to work with artists at various points in their careers as a curator, and it’s always amazing to work with artists like Ming who are constantly creating new ways of looking and thinking about their past work.

CULTURED: Ming, in devising this project, was there a particular facet of your work that you were particularly invested in highlighting?

SMITH: Well, I love working with curators, because the collaboration makes you grow too. I felt vulnerable in a way, as I was questioning the adoption of a larger format, and the editing. There were pieces that I had overlooked, or was unsure of. Sometimes, I keep things for 15 years and don't show anyone. It's hanging on my wall, and I'm still thinking to myself, Is this good? I scrutinize my images. The curators ended up choosing a few of the works that I argue with myself over, and it felt like an affirmation for me. So, I love that discovery process.

CULTURED: Thelma, you describe this exhibition as a “critical reintroduction” to Ming’s work. I'm curious what that phrase means to you.

GOLDEN: It's a project—that's what's so great about this collaboration with MoMA. We can leave behind dogmas of certain exhibition types and work with an artist to define a new way of accessing and presenting their body of work. So, it doesn’t fit neatly into any category. The exhibition takes a swath of Ming's practice across time, across themes, and ultimately brings them together, [offering] what Oluremi and I hope is a new narrative around Ming's practice—one that looks back but also looks toward her work in the future. I want to ask you, Ming, given this deep dive we've taken into looking at your work, installing it, opening it, what are you thinking about for the future?

SMITH: Just continuing my work and being able to lead. Somehow, I'm in a different position, because now the younger generation is looking at me and asking me questions. More than anything, there's opportunity now. Some young girl can say, “I can be in a museum. I can make work for my authentic self, and it is valuable.” That's a path that they can choose. Before, you couldn’t think in that way. We all don't fit into taking the academic path. Some of us are just artists, we’re in tune that way, we have always been that way. My younger self was always searching for that recognition.

CULTURED: After the project debuts, you will travel to LA to show at Frieze with Nicola Vassell. Tell us a bit about that show and the feeling that went into it.

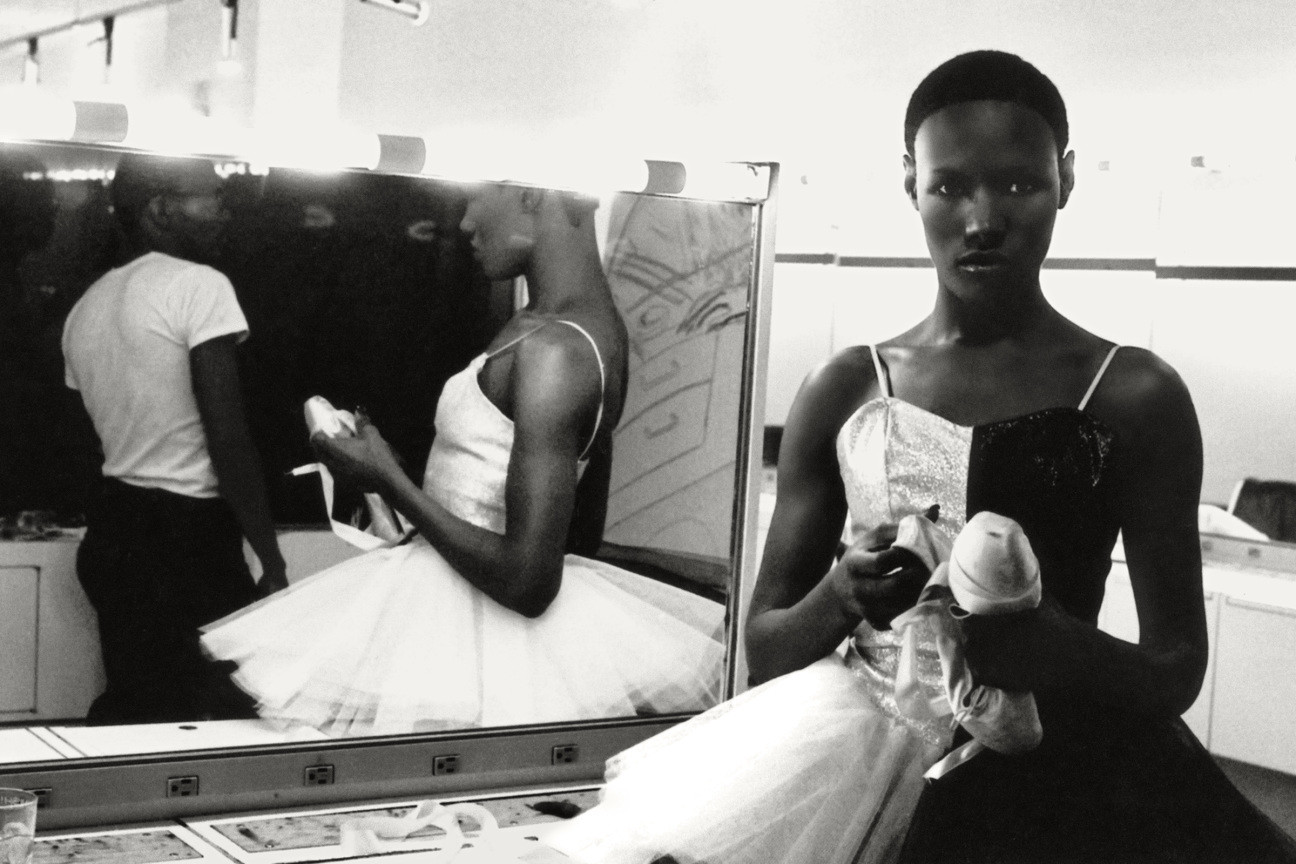

SMITH: Nicola is showing works that haven't been seen before and it’s really exciting. It’s about female energy, which I think really fits the time, and it's needed. The show includes photographs of extraordinary women, all of which came out of my experience—namely Grace Jones, Phyllis Hyman, Tina Turner, and Alicia Keys. Grace Jones was a friend. Before she moved to Europe, she was not “The Grace Jones” the world knew. She was struggling. Our friendship was born from conversation about our shared woes. I first met Phyllis at a shoot for Encore. She was doing the makeup and I was the photographer. I had never shot fashion before and Phyllis—a beautiful six-foot-tall woman, a powerful singer of the blues—looks at me and says, “All the models go in the other room.” She points to me like, Get out of here. I said, “No, I'm the photographer.” We became friends after that, but she was giving the attitude. I photographed her, and later, after she committed suicide, I painted over it. I was going through a gallbladder attack and I was in so much pain, and I identified with her experience of agony and used it to paint. I shot Tina Turner when she released the first album that she did after breaking up her ex-husband. I was working as a dancer in the video along with all my friends. So, I shot her then. Then the video came out, and all my friends that were in it with me died right after because of the AIDS epidemic. That was my family, and they all died. So all these photos are of iconic, powerful women, but they didn’t come out of photography assignments. They came out of me living.

"Projects: Ming Smith" is on view through May 29, 2023 at MoMA. "The Things She Knows" is on view through February 19, 2023 at Frieze LA.